The History of Portola

Written by Rebecca Rhode | Student Project

The town of Portola, California, sits along both sides of the middle fork of the Feather River, in Plumas County, on the upper eastern part of northern California. Portola lies off the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada. The local landscape is best described as being part of the Feather River drainage, which flows westward down the Feather River Canyon. Portola has an interesting history, although there is little published information on its beginnings. This report describes roughly the first twenty-five years of the formation of Portola, with brief background information on the prehistory and history of the surrounding area, to help set the stage of introduction of the town`s place in California history.

About five miles to the east of Portola, the headwaters of the middle fork of the Feather River spring forth in Sierra Valley, the largest valley in North America above five thousand feet in elevation. Sierra Valley is important to the settling and establishment of Portola due to its location, ease of travel, and ease of passage between the rugged mountain ranges and the steep Sierra Nevadan terrain. In the 1850`s, James P. Beckwourth, a self-described mountain man, trapper, and explorer, becme the first white man to settle in the region (Beckwourth was actually part African American and part American Indian). Beckwourth built a house and trading post where the town of Beckwourth is today. His trading post became a stopping place for many travelers heading east to west, especially those lured by the California gold rush of 1849.

Before Beckwourth settled in Sierra Valley, the surrounding region was home to Maidu and Wahoe Indians. The Maidu held most of the land along the Feather River, while the Washoe claimed Sierra Valley and Long Valley. Little is known of the exact numbers of Native American populations in northeastern California and the Portola area, and whether they stayed in the area year round or just seasonally. There are, nonetheless, traces of Native American culture in the form of seed grinding holes in local granite and basalt boulders along the Feather River and nearby hills, in addition to arrowheads and other artifacts found in and around Portola and Sierra Valley. With all the native game species such as deer, small animals, and fish, Portola and the surrounding area has been home for native peoples for hundreds of years.

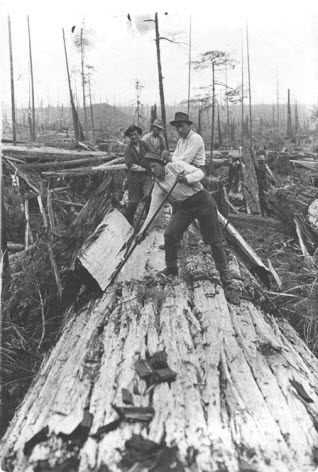

Like many other towns in the northern California Sierras, Portola was founded on the industry of logging. In 1905, lumbermen from the nearby city of Reno, Nevada, came into the Portola area only to find large stands of pine and fir trees. The Roberts Lumber Company logged on the north side of the Feather River, while the Reno Mill and Lumber company worked the south side around Beckwourth Peak. More logging companies from other areas also began to survey and harvest trees from the surrounding hills. In 1905, the Portola area got its first name, `Headquarters,` after a small logging camp with about one hundred men. Soon, thereafter, another group of loggers from Utah settled into the area, and the camp became `Mormon Junction,` and shortly after, in 1908, `Imola`. Several saw mills were built to process the logs. Kerby Mill, located near Grizzly Road and Highway 70; Roberts Mill, located on A-15 just south of Portola; Delleker Mill (Old Gibson and Spencer Mill), located in the town of Delleker; and Clairville Mill, located six miles west of Portola (west end of Fillipini Flat, or Delaney`s Valley), were all early mills in the area. Another mill, located on the south side of Portola where the little league fields are today, also served the area early on.

With all the logging going on, the railroad soon followed. The railroad was necessary to move both unfinished and finished timber from the local saw mills to distant towns and cities for further processing. In addition, many logging spurs were built into local hillsides and ravines to bring fallen trees to the mills. Steam donkeys and teams of oxen and harnesses were also used to lift and carry the heavy logs. On Beckwourth Peak, lumbermen also constructed wooden log chutes. These wooden chutes ran in sections downhill and were greased so that logs could skid downward and be guided to flat ground or into the Feather River, where they could be floated to nearby mills.

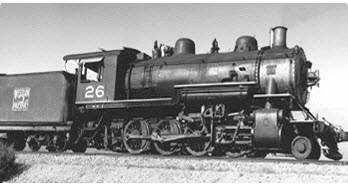

The first railroad into the Portola area was the Sierra Valleys Railroad. In 1885, the California Land and Timber Company began the Sierra Valley to Mohawk railroad, mainly for delivering goods to and from Reno. This operation came to a halt due to financial reasons. In 1894, Henry Bowen bought the railroad and land, along with Kerby Mill (on Grizzly Creek). Two other nearby railroads, at that time, were already completed and in operation. The Boca and Loyalton, which ran from Boca, near Truckee, to Loyalton. and the NC&O (Nevada, California, and Oregon), which ran north-south along Long Valley and Highway 395 from Oregon to Reno. Bowen sought to link Portola and Sierra Valley to the NC&O and the Boca and Loyalton.

Finally, in 1903, the Sierra Valleys Railroad was completed between Hallelujah Junction and Clio. The railroad tracks ran on the north side of the Buttes in Sierra Valley, north of Highway 70 and the Feather River today, through Beckwourth and Portola, with a depot where the Gold Rush Sporting Goods Store is today, continuing westward past Delleker, Clairville, and Clio. The Sierra Valleys Railroad quit running by 1911, due to financial problems. However, by then, the Western Pacific had been completed on the south side of the Feather River, and it became the main railway through the region. In 1910, Portola was served by three railroads: the Boca and Loyalton (B&L), the Nevada, California, and Oregon (NC&O), and the Western Pacific.

One of the most under-heralded figures in putting Portola and Plumas County on the map, literally, was Arthur Walter Keddie. Born in Scotland in 1842, Keddie came to California as a civil engineer and surveyor, and soon thereafter made his home in Quincy. In 1863, he began surveying and mapping the Feather River Canyon and Plumas County. The map was the first of its kind locally, with remarkable detailing and uncanny accuracy. But the map was only the beginning of several more important achievements. Keddie is also credited for the construction of the first telegraph line into Plumas County in 1874. His two crowning achievements, especially in respect to Portola, was his survey work and engineering of the Western Pacific railway from Oroville, through the Feather River Canyon, Portola, Sierra Valley, and on into Reno.

The completion of the project in 1910 made Portola a prime stop on the trans-continental railway. Keddie, known to many as `the father of the Western Pacific,` would also be instrumental in overseeing the construction of a state highway along the same river route.

Along with the railroad, logging, and farming operations, more and more families began to settle into the area. between Beckwourth, Clairville, Portola, and Mohawk Valley, the population grew to over five thousand residents. Stores, saloons, and other businesses formed to serve the growing population. The town finally settled on its namesake, but not before one more name change to `Reposa` in 1909. In 1910, Virgilia Bogue, queen of the 1909 Portola Festival in San Francisco and daughter of Virgil Bogue, a prominent local engineer for the Western Pacific, suggested the name `Portola` in passing, and soon thereafter, in a town meeting, it became official.

With the completion of the Western Pacific Railway through the Feather River Canyon in 1910, Portola was an ideal location for a depot. The town of Clairville, however, would become a ghost town in a matter of a few years, since it sat on the north side of the Feather River and its narrow gauge rails became obsolete. Many of the Clairville residents and their businesses would pack up and move to Portola. Some of the buildings were also torn down and relocated as well. It is perhaps possible that had the Western Pacific taken over and retrofited the Sierra Valleys railroad route between Clio and Sierra Valley, then Clairville and Delleker would still be the bustling communities they once were before 1915.

In 1907, the first hotel in Portola (probably still Imola then), the `Home Hotel` was built. In 1909, the first grammar school was established on the north side of town, called `The Little Red School House.` It burned down in 1911, and the school was moved to the south side of town. Portola`s first high school was built in 1921, somewhere near downtown Portola; but it too burned down in 1925 and rebuilt at its present location in 1926. Fires were very common and many buildings, mills, and entire blocks burned to the ground in the early years. In 1928, a huge fire destroyed twenty-six homes and businesses along Commercial Street in Portola, from the southern end of the Gulling Bridge and halfway up Commercial Street.

The main problem was a lack of a water system. In 1908, water was delivered in town by bucket and sled from nearby creeks and springs. By 1908, streets were platted by the Reno Mill and Lumber Company. In 1910, Ed Lane established the Portola Water Company. Underground pipes were dug and placed; however, there were no pumps. A large wooden water tower was built at the west end of town. Before 1915, there was no electricity in Portola, and lights were powered by kerosene. Grizzly Electric Company, in 1915, introduced the first commercial electricity in Portola. Electricity was only available at night at that time, and until 1928, it was used solely for lighting. Residents were charged ninety cents per light, businesses were charged one dollar.

Much of the historical information on the area was recorded from local news sources from the era. In 1866, the Plumas National began collecting news in Plumas County. Most of the stories covered mining and farming activity centered on Quincy, Johnsville, Jamison City, and other local communities. Farming, dairying, and other local actitvities, were often mentioned from the towns of Beckwourth and Smiths Neck (Loyalton), and from ranches around Sierra Valley. In 1892, the Plumas National became the Plumas National-Bulletin. This would be the primary source of information for most of Plumas County for the next twenty-five years.

In 1910, another newspaper, the Portola Gazette, established itself for about two years, when it eventually folded. In 1916, the Portola Sentinel came off the presses until 1927, when the Portola Reporter took over and still operates today. These old newspapers are an invaluable resource for looking back in time on the history of the region, and many of the stories chronicle the successes and failures of towns, townspeople, and businesses.

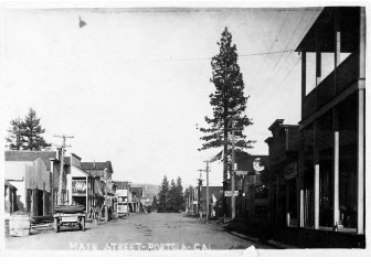

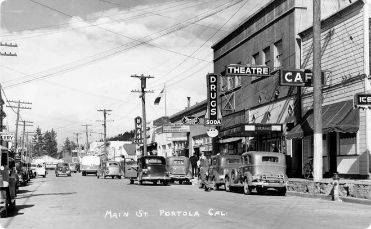

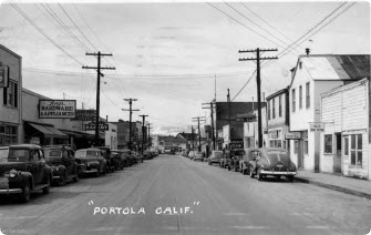

The Feather River has divided both sides of Portola since its early days as a lumber camp. Commercial Street, on the south side of the river, and Riverside Avenue, on the north side, both held early businesses and residences. In order to travel across the river, the first bridge was built where Beckwith Street is today, at the east end of town. The bridge was actually a foot bridge, where horse-drawn wagons and sleds could travel freely. A crude rope bridge was also strung across the river on the western end of town. Around 1910, railroad tracks ran on both sides of the river, so the bridge actually ran from track to track. Commercial Street, around 1910, had several rooming houses, blacksmiths, mercantile stores, and more than several saloons. A `red light` district existed on the southeast end of town.

Downtown Portola has undergone many changes in businesses, although most of these changes have been made by name only. The buildings in the downtown area have had numerous facelifts, having survived fires, structural changes, and occasional improvements. In 1928, the wooden baseboards and dirt streets were replaced with concrete sidewalks (partially) and asphalt streets. By 1930, there were over thirteen saloons, with many having poker tables, slot machines, dice, blackjack, and a Chinese lottery. One of the first stores on Commercial Street in 1910 was the Racket Store, and supplies mainly came from Reno, Sacramento, and San Francisco.

For almost one hundred years, Portola has kept its small-town image as a `railroad town.` There are many towns like Portola in northern California that were born out of early mining and lumber camps; some have preserved their unique place in California history. The railroad industry has seen its importance become less and less, and this is perhaps why Portola has not grown leaps and bounds like other California cities. It is no coincidence that most of California`s logging towns have pretty much kept their bucolic, small-town image, perhaps eternally constrained by geographic and economic factors. Downtown Portola still has some of its original buildings and sidewalks. Local newspapers still hold the archives of the development of Portola and its surrounding community. A few longtime residents still carry valuable memories of early Portola. All of these resources preserve what little we know about the local history.